La munda fabricada

My name is Veralyn Sage Aldritch. Sage comes from my mother, Aldritch from my father, and Veralyn is a derivative form of Vera, which comes from the Latin word for truth, verus. It's a lovely name, isn't it? I always believed a name like mine should belong to somebody very important.

I am widely known as an art collector, contributing to the field of fine arts through buying, selling, and trading great masterpieces. My private gallery, home to rare works created by the likes of Beauchamp, Kashani, Caillier, and van der Lucht, is located in the heart of the Château de Aldritch, a manor that I inherited from my father, Charles Aldritch, who was widely considered one of the greatest sculptors in his generation. He rose to fame because of his style, a modern interpretation of the ornate drama that defined Baroque art, often being cited as a "father of the neo-Baroque movement."

Many art collectors have their own secrets, but I have one big secret that would turn the world upside-down. And calling it a secret is an understatement; secrets like mine are their own worlds.

There is no better way to explain my world than to immerse you in it. I am an art forger. My world is all about targets, fortunes, and styles. Just about every painting hanging in my gallery is my own creation; the world-famous Der Zorn Gottes, a supposed lost work of Helmut Niemann, was painted with my own hands about fifteen years ago in the Chamroeun Chamber. I sold it for the equivalent of thirty million dollars in an absurd offer presented by the Goethe family.

How did I get away with it?

Once unbeknown to the world, the Aldritch family had been in possession of Niemann's diary since Maximilian Doherty gifted it to my father. I was able to identify the brand of ink Niemann used in the Chamber, and forged a line in an early entry detailing his various works. As it best translates:

Man's Acquiescence will embroider the Love detailed by the Wrath of God, whose Image I may describe as most genuine, most fulfilling, most venerable.

The forged lines, just like the rest of the diary, were assumed to be authentic after a thorough examination from the Niemann Institute. Shortly after my father donated the diary to the National Museum, Der Zorn Gottes became all the rage among the elite. Many interpreters were disputed in the significance of the work, but the "correct" interpretation would believe the work served as a gateway between Niemann's earlier classical work and his later, more daring endeavors in oil painting.

The trick in feigning authenticity is becoming authenticity itself. Most forgers lack any of the following:

- the right materials.

- the right methods.

- the right mindset.

- the right environment.

- the right background.

I was able to mimic Niemann by replicating his setting. I used the same Italian canvasses Niemann used in works such as Zu verachten and Dem Trinker, the same dated pigment brands he used throughout his life, and old German paintbrushes available only during the stretch of time when the painting could have been conceived. Painting Der Zorn Gottes was, of course, the difficult part.

In order to paint a Niemann, I had to be Niemann. And in order to be Niemann, I had to know Niemann. Knowing that the details I remembered from the diary would not be enough to distinguish to an audience Veralyn Sage Aldritch with her knowledge of Niemann from Niemann himself, I set out in pursuit of gathering more information.

My favorite part in that endeavor was disguising myself.

But I must digress! In considering that memories of the past wilt the flowers of fresh thought, I must refrain and reconcentrate. I recently rediscovered myself as an artist, and I have now a new creation to present to the world: Hugo Manuel Guertena, renowned for a mysterious work called La munda fabricada. Prized for its sacrilegious unconventionality in a time when merit depended on regularity, La munda fabricada is a cult craze among snobs obsessed with obscurity, magic, etc. and socialism.

Guertena, likewise, has quite the reputation. His work is seen as extremely peculiar for his time, and La munda fabricada has frequently been brought into question for its legitimacy. Theorists went insane over the origin of the painting; some believed Guertena was an artist that shaped the underground art scene, some believed the work belonged to somebody else, and some believed that Guertena was a time traveler. Unfortunately for the Guertena family, the painter was indeed confirmed to be legitimate (i.e. by Guertena) only after they had sold the painting for about one hundred thousand dollars to the Museo Milado. The Museo Milado eventually sold the painting to the national museum for six million dollars—would you believe it?

But the mystery behind Guertena is arguably what makes him so troublesome to monetize. He maintains a mythological reputation among the public, but collectors hardly budge out of concern for a severe lack of information about his background. His family barely remembered him as an artist, and only four works of his have been confirmed to date:

Fallecimienta de la Individua, three headless statues each wearing different clothing. The piece evinces Guertena's disapproving sentiment of marriage, using a wedding dress in the middle to divide a bruised housedress (denoted "nacimienta") from a casual, well-kept nightgown (denoted "fallecimienta"). Guertena's unusual suffixes arguably color the work in a feministic light.

Dama en la Roja, a portrait of a woman wearing a red dress. Urban legend says that the woman in picture is said to be Guertena's lover, but there is nothing to substantiate the claim.

El Ahorcado, a picture of a hanged man. Though hardly popular for reasons similar to La munda fabricada, El Ahorcado was widely sold for a limited time as a tarot card.

La munda fabricada, an inexplicable painting depicting "the fabricated world." Because so little is known about its actual background, I will go over the visual aspects that are most widely talked about.

Modernity: Guertena lived during a time when avant-garde art extended only as far as playing with impressions. Almost all visual art in that era maintained a realistic form, a line which La munda fabricada walks along too loosely.

Duality: The left side of the picture seems to be more conventional compared to the right side.

Inconsistency: The brushwork here is extremely strange. Parts of it appear to have been painted with careful layered brushstrokes, while others have been smeared over with out of place lines. Many strokes seem to be brushed over with other tools, like sponges.

The top right: A figure composed of rigid squares seems to be poking out near the top right corner. What might that be?

La munda fabricada

But what might I mean by calling Guertena my newest creation? Guertena may now be appreciated in certain circles, but I want to make him big. Many have tried doing something like that, but nobody could get away with it like I can. Stylistically, Guertena is just my thing. Innovative, perplexing, contradictory, and volatile. Creating a Guertena may be both very easy and very hard; because he barely exists, Guertena must be created, and how successfully that can be done just depends on how much of an artist a copycat really is.

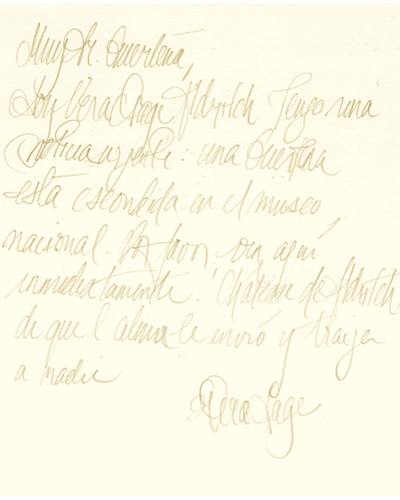

Un bienintencionado infierno, un lugar inalcanzable, and Belleza de vacío are all works I painted for the national museum. Today, I will be planting them in the garret, a storage compartment I discovered during my time disguised as a security guard named Samuel Ire. I believe the curator himself was unaware of its existence based on how the scandal unfolded back then, but I am admittedly unsure if it is in use today. I have been in contact with Sarmiento, the curator, for a long time, but never did it cross my mind to ask him about that. Perhaps that distances me even further away from suspicion.

Something that I am aware of, however, is that a certain custodian has been working at the museum for twenty years. I last met Sarmiento four weeks ago, where we briefly had a very brief, but friendly exchange with the old custodian, Matteo. Disguised as him, I may be able to sneak my way into the attic without suspicion. But in order to do that, I will need two disguises.

In other news, I have just arrived in Madrid.

I am, in a way, currently disguised. That is, I am wearing my private face around town today. I packed a suitcase for just the very bare essentials: nine paintings, two changes of clothes, a bag of dust, a basic disguise, a rope and hook, a rolled-up yellow banner, and several rubber bands. Is there an inn close by? I'll set out at five to set down my paintings.

"Oh. I'm new here, sir. I just started today. I think I'm lost."

Matteo seems relieved. I didn't get the time just right for the shift, but I ran into Matteo in a very timely encounter. I'm disguised as "Ernesto," but my dropped voice intonation barely passes as masculine. Matteo would never figure that out, but it is worth noting that he might just be the only person in the world I could fool. Luckily, the uniforms they use here are still the same as ever, and I was able to recycle my Samuel outfit to feign my role as a custodian.

"Ah, why didn't you say so? I am in charge of this gallery. We could use a helping hand in the upper quadrant. Is that where you were stationed?" he asks, gazing at me expectantly.

"Forgive me, sir. I don't believe I remember where I was stationed. I was given a letter and a number, but it's since slipped my mind."

"Would it be 4-B?"

Ouch! He's not as simple as he seems.

"4-B? I don't think so..."

He chuckles. What a strange dog!

"Follow me," he says, leading the way to the stairwell. Oh, wouldn't it be wonderful to be placed near the garret?

"Right… here. The one who usually give me a helping hand in this room are all away today. The others here don't budge. But you're at my mercy!" he smiles, and I beam in return. "See those statues gathered over there? All new arrivals. You can see I'm getting really old, right? I could use a young boy's strength to lift those onto the pedestals.

"Oh! And check if there's anything that was left behind in storage. I'm sure you know where that is," Matteo remarks, eyeing my uniform.

"You got it!"

I give him a thumbs-up as he leaves the room. Thank goodness I cut my nails. But could that scenario have played out any better? I now have an invitation to the attic, from where I can easily access the garret.

But I am now facing a very immediate problem. If I am going to leave my task behind entirely, Matteo might have to move the statues himself. Poor old custodian! He's such a sweetheart; I shouldn't do that to him. It may be necessary to leave the statues alone if I were to frame Matteo as senile and distort reality to make Ernesto as a fictional character, but I lack the cruelty to put the custodian in such a position of scorn and question.

I have a better idea.

Following a frenzied blitz of haphazardly placing three-stone busts on pedestals, I finally made toward the garret. I very briefly considered carrying one of the statues with me to the regular attic so that I could cook up a story if I were caught in there, but I decided against it. I think I made the right decision.

As I guessed, the garret seems to be in very mild use; its inaccessibility is made apparent with how little is stored in here. Dusty paintings placed on racks line the walls. A miniature Greco-Roman statue is placed in front of the room. An old coat hanger sits in the corner. I wonder what they store in here.

Unsurprisingly, these paintings all belong to obscure, insignificant, or forgotten artists. I only recognize Monteil, Araso, and de Salaga among them, none of whom would ever be hung in a respectable gallery.

I climb back down into the attic, pressing up against the window. I left the three relevant paintings behind a bush down below, so I simply have to hope I aligned them correctly with the attic window.

It seems like hope wasn't enough! I look down and see the three paintings, thankfully, but I placed them rather inconveniently. A crescent moon shines brightly in the sky. Is it really true that the sky is darkest during a new moon? The towering church across the street casts a dark shadow along the museum wall, although it be that this shadow only covers about half of the building. I didn't quite anticipate there being a shadow here to begin with, but I should not assume it will play grace tonight.

I remove the banner rolled up around my left leg. On second thought, this banner seems far too long for its width, but I have no better substitute to execute this trickery. I roll the banner down the window, some spectators briefly glancing at me before moving on; I hang the banner from my left hand, while I reach into the uniform's large pocket with my right.

I pull out my rope and carefully drop its line, hoping to hook one of the paintings through the foot-long rings I attached to their frames before leaving the inn. My suitcase is somewhere inside the bush, too, isn't it?

I think it took me a good ten minutes for the first one, Belleza de vacío. It felt like fifty seconds, but moments like these flurry by. Ten minutes was far too long.

As you may have guessed, I am no longer in the attic.

"Sir?"

"Hm?"

"I don't think I'm at the right museum."

"What do you mean?"

"I think I'm supposed to be a custodian at another museum in town. I found a pamphlet upstairs and recognized the name of the museum where I applied."

"Huh? I know you're directionless, but how could you mix up a museum?" He smirks.

Hmm.

"I come from a small village in Andalucía. I'm not very familiar with the urban environment."

I would chuckle here, but laughing would be a terrible idea for this voice.

"Oh, boy. Who let you in here, anyway?"

Hm, hm, hm. That's tough.

"It must have been the manager, right? He gave me my uniform and told me to meet you."

Oh, no. I made it complicated again.

"He told you to meet me?"

"I think so?"

Matteo does his chuckle again, and relief dawns over me. Ditziness is maybe the most dangerous trait a persona can have. It is awfully convenient, a skeptic would opine, to forget details that would hinder your legitimacy, and that by nature reeks of suspiciousness. I wouldn't dare try this stunt with a figure like the curator.

"I'll take your uniform back. Did you do that thing I asked you to do with the statues?"

I take off the uniform and hand it to him. My best option requires a sacrifice. How tragic!

"I did, sir. Thank you very much for your help."

Maybe it would have been best to keep quiet, but I couldn't resist breaking out of character.

"Oh, also—in my village, we had many fortune-tellers. One of them once told me that I would meet somebody committed down to his soul, and that I would find myself thanking this person before finally parting ways. You're a very dedicated person, and I really appreciate your service to this museum… and to art. Have a wonderful evening."

The message, at the very least, was sincere; I return his smile before walking away.

I leave the room, hearing his footsteps moving further away. This is my chance. I dash for the left staircase, making my way back up to the attic. I cannot be seen. There may be some twenty or so people left in this building

|  |