full context:

the cognitive functions

There are some things on the Internet that have led people astray: they confuse, they mislead, and they misinform. Among these are the cognitive functions, a concept that most people in the online typology community are aware of, but one that only a few really understand.

introduction

just what is there to understand?

Many typologists who involve themselves with the cognitive functions begin their journeys with fascination.

This is pretty weird! But so many people talk about it.

In fact, there's so much about them here on this website!

But I don't get what it is exactly…?

Oh, they say there will be a lot of misinformation?

There are good sources and bad sources?

Stereotypes, biases, and conflicting information?

So it's up to me to figure this all out?

I guess I'll give it a try.

This is a guide, a tale, a persuasive essay, and ultimately, a resource. Whether you are well-acquainted with the cognitive functions or happen to be a novice looking for information, I promise that you will have been exposed to information you had previously not known, ideas you had previously not considered, or the perspective that I will encourage you to adopt not only about the cognitive functions, but regarding typology as a whole by the time you have read through everything I will present.

A forewarning: Depending on what you currently assume about the cognitive functions, many of the ideas I will present to you may be met with immediate judgment and disagreement. I humbly beg of you to put aside your preconceptions before considering the following and to consider the following in full and with genuineness. Because as it turns out, this will be imperative in opening yourself to understanding what the cognitive functions really are.

We will be unraveling all kinds of ideas that different people with different perspectives have shared about the cognitive functions, and I strongly emphasize that I do not intend to expose you to an exhaustive list of refutations to swear by. There are no sides, and there is no debate. The ideas will not matter here as much as the perspective behind these ideas will.

Now, shouldn't we start by explaining what the cognitive functions are? Yes. But there is a specific way that I would like to do that—we will first examine how the cognitive functions came to be the way they are today. This is especially important because today, typologists' ideas of the nature of the cognitive functions differ so much from one another that it is extraordinarily difficult to draw exactly where they share common ground and how we can define the concept concisely without contradicting any particular typologist.

You, as a modern-day typology enthusiast, may express concern over which ideas are legitimate and which should be ignored. Looking into the origins and history behind the cognitive functions should aid you in this journey. And so we begin…

chapter 1

a history of the cognitive functions

The cognitive functions begin with a concept in Myers-Briggs theory called "type dynamics." Type dynamics describe the interaction between two or more preferences in a Myers-Briggs type. Geyer (2005) puts it more descriptively: "Type dynamics can be briefly defined as the interaction of type preference in a systematic, but linear form, according to a person's type code, from most preferred to least preferred."

It is no mystery that Isabel Myers' theories about personality were in part derived from Jungian literature, specifically regarding Jung's work in Psychological Types. However, acknowledging this does little to show that Myers largely strayed away from Jung's conception of the four functions (thinking, feeling, intuition, and sensation) and was largely focused on both her four dichotomies (EI, NS, TF, and JP) and the nature of the extraverted function.

Some context behind this is illuminated by reckful on Typology Central:

Myers was a nobody who didn't even have a psychology degree — not to mention a woman in mid-20th-century America — and I assume that background had at least something to do with the fact that her writings tend to somewhat disingenuously downplay the extent to which her typology differs from Jung. So it's no surprise, in that context, that the introductory chapters of Gifts Differing, besides introducing the four dichotomies, also include quite a bit of lip service to Jung's conceptions — or, at least, what Myers claimed were Jung's conceptions — of the dominant and auxiliary functions. But, with that behind her, Chapters 4-7 describe the effects of the "EI Preference," the "SN Preference," the "TF Preference" and the "JP Preference," and those four chapters total 22 pages. Chapter 8 then describes the eight functions — and that chapter consists solely of a half-page table for each function, for a total of four pages. What's more, those four pages were simply Briggs' summaries of Jung's function descriptions, and Myers ignored (and/or adjusted) substantial portions of those in creating her own type portraits. (As one example, Myers' IS_Js bear little resemblance to Jung's Si-doms.)

Let's look a little deeper. In the early 1940s, Katherine Briggs and Isabel Myers developed a questionnaire based around Jung's work to test for psychological type. With it came a new development called the judging-perceiving axis, which, on Form C, identified whether the judging function was extraverted or the perceiving function was extraverted. This was unlike another type instrument released around this time called the Gray-Wheelwright Jungian Type Survey, which excluded the J/P facet altogether.

However, Jung's typology was greatly unlike what Myers and Briggs adapted into Form C: Jung did not think in terms of "extraverted functions" or "introverted functions" as Myers did but rather in terms of types with subjective or objective focuses dominant in a particular function. The trouble here is in how Myers interpreted function attitudes. The expression of a function is not necessarily internalized or externalized, but simply that there was a predominant focus in how it was expressed. Adapted from Daryl Sharp's Jung Lexicon:

Subjective level. The approach to dreams and other images where the persons or situations pictured are seen as symbolic representations of factors belonging entirely to the subject's own psyche.

Objective level. An approach to understanding the meaning of images in dreams and fantasies by reference to persons or situations in the outside world.

Myers introduces a new function in the auxiliary position to balance out the direction of the dominant function, but Jung did not believe a lesser function would express itself in such a way. Conceptually, his idea of type is worlds apart from how Myers incorporated it into her type dynamics. It can be extrapolated that when Myers applied strict directions to her type dynamics, she needed to reflect in them the nature of the dichotomies… and so, we are given justification for how Myers characterized the J/P dichotomy.

Myers and Briggs have asserted that type dynamics follow a developmental model: one function assumes a dominant role early in life, a secondary function differentiates during teenage years, and a tertiary function comes about in mid-life… while the inferior function tends to be unconscious and is evident in high stress situations (Naomi Quenk (1993, 1996, 2002) dwells on the concept of inferior functions and being "in the grip").

The roles (specifically the directions) that each function will assume have been debated. Myers herself does not spend much time exploring the lower functions in type dynamics. The MBTI Manual today (3rd edition, 1998) describes the following as the order for the functions:

dominant: primary direction, dominant function

auxiliary: opposite direction, auxiliary function

tertiary: opposite direction, opposite function of auxiliary

inferior: opposite direction, opposite function of dominant

e.g. INFP is dominant introverted feeling (Fi), extraverted intuition (Ne), extraverted sensing (Se), and extraverted thinking (Te)

In 1983, William Harold Grant, Magdala Thompson, and Thomas Clarke authored From Image to Likeness: A Jungian Path in the Gospel Journey, a book that "correlates Carl Jung's psychological types with Gospel themes and Christian values… [and] links the categories of the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator… with corresponding virtues and forms of prayer." The authors present four different models in this book, of which the second and third are based on Jung's personality theories; the third model "views Jung's functions and attitudes on the basis of a developmental typology." This model was based on their observations from several hundred people involved in their retreats and workshops along with thousands of students from two universities; it specifically referred to four stages of development from the ages of six to fifty.

The authors understood this model deviated from conventional interpretations of Jung's work and did not expect to "find support within the Jungian tradition." They also write: "admittedly, it needed further testing," denoting that it is an experimental model. This model was included in the book in order to encourage people to view their personalities dynamically rather than statically. The model presents its own "function stack":

1st period: primary direction, dominant function

2nd period: opposite direction, auxiliary function

3rd period: primary direction, opposite function of auxiliary

4th period: opposite direction, opposite function of dominant

e.g. INFP is dominant introverted feeling (Fi), extraverted intuition (Ne), introverted sensing (Si), and extraverted thinking (Te)

There is no rationale provided in From Image to Likeness for why the model claims that the tertiary function is in the same direction as the dominant function. However, according to Peter Geyer, type dynamics had become a disputed topic in the 1990s because there were now two different versions of it: the Jung-inspired Myers model in which there were only two directions (IEEE or EIII without any switching of the directions in between), and the "balanced" Grant model with its four directions (IEIE and EIEI). At the time, the MBTI Manual (1st edition, 1985) referenced Myers' model with a footnote for Grant's model.

Geyer writes:

I discovered later, through various conversations, that Grant apparently claimed his position to have come from Myers herself, which is interesting given the paucity of her written work on the subject. From my reading and research, she seemed more interested in dominant and auxiliary than anything else, rather than the predominantly unconscious functions. This she called shadow, not making a connection between that term and the Jungian archetype. Her apparent later acceptance of or agreement with Grant's position just before her death, has been attested to by Kathy Myers, and I believe it should be taken in the context of her lack of interest in "the dark side", as her son Peter has recently put it (2001).

Nevertheless, Grant's model has played a pivotal role in the evolution of type dynamics, and his basic model outline is overwhelmingly reflected in cognitive function stacks today. Geyer postulates five reasons for its success: its specificity, its accessibility, and its applicability in training environments, as well as Grant's status as an early MBTI user, and that influential people drew inspiration from the model (most notably, Grant had influenced the creation of eight function models (see Beebe, the Hartzlers, Berens, Thompson) that are still used today by many).

With time, Grant's model had come to be preferred over that of Myers. Bill Jeffries writes in True to Type (1991):

Where the disagreement exists is in regard to the attitude in which the tertiary function is expressed. Those who authored the Manual hold to the view that the tertiary function is introverted for extraverts and extraverted for introverts (p.18) I, along with Grant, Clark, Thompson, Kroeger, and others disagree. We hold to the view that the tertiary function is always "in the same attitude as the dominant function" (Manual, p. 294, note 10)…Experientially, the view represented in the Manual makes no sense to me or to those whom I know. Theoretically, the issue of balance in type theory also leads me to my view. If one way to see balance is to see it as teamwork between the extraverted attitude and the introverted attitude for the dominant and the auxiliary…by extension it would seem logical (I am a "T") that the same balance should exist between the attitudes of the tertiary and the inferior functions…There needs to be balance among those functions predominantly in the unconscious as well as those predominantly in the conscious part of our personality.

Naomi Quenk's 1996 publication In the Grip: Our Hidden Personality finds a caveat around this debate by adding a footnote beneath a table of type dynamics (in which a direction for the tertiary column has been left out): "Note that an attitude (Extraverted or Introverted) is not specified for the tertiary function column, as that function may be associated with either attitude." Interestingly, she elaborates on this idea by saying that "a person's tertiary function may be used in either direction, depending on circumstances or individual habits." Before Quenk's literature on the inferior function, the lower functions (tertiary and inferior) had been strongly neglected by type dynamics theorists. Alan Brownsword in It Takes All Types! makes a note of how the tertiary function hasn't even been given a proper name, calling it "the third function" before moving on.

But how, you may ask, have the functions in type dynamics been defined? How were they historically defined? Do they differ today? If so, how?

Isabel Myers placed emphasis on the notion that judging and perceiving is extraverted. Her focus on the dominant and auxiliary functions was centered around satisfying this particular constraint: even though INFP is an IN type, it is dominant in introverted feeling and auxiliary in extraverted intuition because it is a perceiving type and hence what it extraverts should be related to its preference for perceiving. This line of reasoning explains why she moved away from the lower (shadow) functions; her IEEE/EIII stacking is noticeably very Jungian in that it has only two directions, but conflicts with the idea of judging and perceiving pertaining to what is extraverted.

Isabel's intentions in harboring type dynamics is one that is difficult to explore, and it would not be farfetched to consider that she created the concept to connect her work more with Jung than to truly incorporate type dynamics into her personality theory. Myers heavily centered her work around her dichotomies, and forms testing for the MBTI have only ever directly incorporated the dichotomies.

Her work with type dynamics, in fact, somewhat mirrored that of her dichotomies: they went against Jungian tradition and focused more on fulfilling the concepts as she had defined them. The following is an excerpt from the MBTI Manual (3rd edition) labeled "The Eight Jungian Functions":

Dominant Extraverted Sensing: Directing energy outwardly and acquiring information by focusing on a detailed, accurate accumulation of sensory data in the present

Dominant Introverted Sensing: Directing energy inwardly and storing the facts and details of both external reality and internal thoughts and experiences

Dominant Extraverted Intuition: Directing energy outwardly to scan for new ideas, interesting patterns, and future possibilities

Dominant Introverted Intuition: Directing energy inwardly to focus on unconscious images, connections, and patterns that create inner vision and insight

Dominant Extraverted Thinking: Seeking logical order to the external environment by applying clarity, goal-directedness, and decisive action

Dominant Introverted Thinking: Seeking accuracy and order in internal thoughts through reflecting on and developing a logical system for understanding

Dominant Extraverted Feeling: Seeking harmony through organizing and structuring the environment to meet people's needs and their own values

Dominant Introverted Feeling: Seeking intensely meaningful and complex inner harmony through sensitivity to their own and others' inner values and outer behavior

These are not an accurate summary of the Jungian functions (with their respective directions)—rather, these definitions seem to revolve more around Myers' dichotomies than they do the four Jungian functions. For example, Dominant Introverted Sensing in Myers' view is about storing facts and details (similar to her idea of "sensing"), while Jung emphasized that the Si type is influenced by subjective impressions of reality. Jung writes:

Above all, his development estranges him from the reality of the object, handing him over to his subjective perceptions, which orientate his consciousness in accordance with an archaic reality, although his deficiency in comparative judgment keeps him wholly unaware of this fact. Actually he moves in a mythological world, where men animals, railways, houses, rivers, and mountains appear partly as benevolent deities and partly as malevolent demons.

Jung also strongly emphasized aspects of "introverted sensation" that were excluded from or were at odds with how Myers would describe Si in type dynamics:

But, where the influence of the object does not entirely succeed, it encounters a benevolent neutrality, disclosing little sympathy, yet constantly striving to reassure and adjust. The too-low is raised a little, the too-high is made a little lower; the enthusiastic is damped, the [p. 503] extravagant restrained; and the unusual brought within the 'correct' formula: all this in order to keep the influence of the object within the necessary bounds. Thus, this type becomes an affliction to his circle, just in so far as his entire harmlessness is no longer above suspicion. But, if the latter should be the case, the individual readily becomes a victim to the aggressiveness and ambitions of others. Such men allow themselves to be abused, for which they usually take vengeance at the most unsuitable occasions with redoubled stubbornness and resistance. When there exists no capacity for artistic expression, all impressions sink into the inner depths, whence they hold consciousness under a spell, removing any possibility it might have had of mastering the fascinating impression by means of conscious expression. Relatively speaking, this type has only archaic possibilities of expression for the disposal of his impressions; thought and feeling are relatively unconscious, and, in so far as they have a certain consciousness, they only serve in the necessary, banal, every-day expressions. Hence as conscious functions, they are wholly unfitted to give any adequate rendering of the subjective perceptions. This type, therefore, is uncommonly inaccessible to an objective understanding and he fares no better in the understanding of himself.

Deferring to Jung with type dynamics is, in many ways, a categorical mistake. Where Jung focused on the dynamic between conscious and unconscious attitudes, Myers focused on conscious and emergent attitudes. Where Jung expanded on the nature of his four functions, Myers expanded on the nature of her four dichotomies.

This leans into an issue that only grows with time: an issue of corruptibility, mischaracterization, and missimplification.

Alan Brownsword wrote It Takes All Types! in 1987, just four years after Harold Grant presented his model in From Image to Likeness. He incorporated Grant's tertiary diversion (that it mirrors the direction of the dominant) and expanded upon it in another book called Psychological Type: An Introduction, published in 1988. Here, Brownsword heavily draws inspiration from David Keirsey and presents detailed descriptions of sixteen personality types centered around Grantian type dynamics.

But Brownsword's literature in particular brings up an important question regarding type dynamics: just how logically connected is this concept to Myers-Briggs theory? Can we certify that type dynamics are indeed a logically derived subset of Myers-Briggs theory—that Myers-Briggs type codes necessarily signify a particular function orientation?

Decades ago, asking this question would be considered unusual because the relationship between Jungian personality theory and the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator wasn't quite sorted out to begin with. Jung's theories carried much more credibility and were treated in a more absolute sense; it may not be wrong for us today to assume that people back then believed there to be a neurophysiological basis for the existence of a "feeling," "thinking," "intuiting," and "sensing" part of the brain. Type dynamics were approached in a manner that sought to confirm a connection between Myers' theory and Jungian psychology by establishing how both were truly connected.

Brownsword prefaces his book Psychological Type: An Introduction by stating that Jungian theory outlines three sets of preferences: extraversion/introversion, intuition/sensing, and feeling/thinking, and that Myers and Briggs added a fourth: judging/perceiving. This is, in my view, somewhat careless of Brownsword. In Brownsword's view, Myers and Briggs' theory acts as an extension—a development—of the already established Jungian theory, and that "psychological type" is a single entity that is composed of bits of Jung, Myers, Briggs, and Keirsey's work.

This is an unfortunate way of thinking that has remained and continues to captivate typologists today. It is the source of much confusion surrounding the now named "cognitive functions" and has misled a great proportion of the Internet typology community into believing assumptions that have hindered the progress of Myers-Briggs theory and typology as a whole. What Brownsword does not realize is that in his pursuit to syncretize various theories into inching closer to a "truer" set of type profiles, he overlooks a fundamental inconsistency between the type codes he borrows from Myers-Briggs theory and the profiles he creates.

The Internet may in large part be responsible for how type theory has evolved from type dynamics to the cognitive functions we know today, and analyzing this portion of its history in the same breath does not do justice to how fundamentally different the two worlds surrounding it in context are.

chapter 2

using mbti as a litmus test

Before continuing with the following section, there are important things to consider. Of these, the most important may be that type dynamics can get something very fundamentally wrong about the human personality, but understanding why it is wrong is an unenlightening experience. This would be the fact that we don't naturally see our personalities in ways that imitates how type dynamics break down the human personality. Consider that if that really were the case, we may already have an intuitive insight into defining personality like that; in other words, we learn the system—not discover it. Describing the people we know is a very subjective process: What do we know about them? What about them do I not know? What about them shines? What about them do we not like? We see people as "beings" when describing their personalities rather than "parts of a whole."

This is essentially a refutation of how many today view the "cognitive functions" (and how many in the past viewed Jungian theory and Myers-Briggs theory). There is no specific, predefined way of processing information that falls into sixteen specific, rigid categories we can call the cognitive functions. This is easy to show from a logical point of view ("can you prove, without a doubt, that the cognitive functions can accurately describe all personalities in consistent, unchanging ways [that define the system]?"), but understanding it intuitively is extremely difficult.

Here is a potentially easy way to understand that: if the cognitive functions accurately described human personalities, our world today would be organized in a way that accommodates for these preferences. Instead, we live in a chaotic world where certain traits are desired or rewarded in certain tasks and areas, but these personality traits are not universalized in a way that the cognitive functions can describe. If human personality were so simple that we could describe our cognition in a reproducible, consistent manner using the cognitive functions, we would already have a grasp for our limits and boundaries as people. Instead, psychology is a new field of science and it has no definite answers for where we end. Consider that a true-to-life system to categorize people would have a category for each individual person because each individual person has a unique personality with unique experience and unique thinking, and that a generalization that places them into categories that betray even one inconsistency with their actual way of being fails as an accurate generalization of their personality. It is both unusual and reductionistic to describe personality in a way that follows this linear pattern, and nothing has proved that personality works in this specific way in a way that is logically sound and empirically reproducible.

But even that may be unconvincing! After all, how can one logically prove the absurdity of personality? How can one prove that personality is better observed as a whole rather than a series of parts? What's with the appeal to science—don't you know that empiricism accounts for only so much?

Something I strongly wish to emphasize here is that using systems with arbitrary constraints on reality is not necessarily bad, but it is at the very least very limiting if it's the only way you perceive reality. There is merit in any system we come up with to describe reality that does not contradict reality; even those that do contradict it are valuable in that we can come to understand how it contradicts reality and why it does so. This is all just a forewarning to not just take a claim at its word—but to understand why this claim is being made and what basis this claim has.

Now, let's continue!

❧ ❧ ❧

In order to understand exactly how Brownsword's conception of type dynamics deviates from Myers-Briggs type theory, we can use Myers-Briggs itself as a litmus test to assess whether not his type descriptions, when broken down, are in line with the Myers-Briggs type that they are describing. For the INFJ profile presented in Psychological Type: An Introduction, Brownsword writes:

iN: The guiding force in the INFJ personality comes from within. When alone, INFJs let their minds wander wherever they happen to go. They impose no structure or order to their mental meanderings. The process that takes place inside is an intuitive one and therefore difficult, even for INFJs, to describe. They have insights on insights and even insights on insights on insights. They just happen. There is no pushing, no effort to it. Feeling judgments support intuition and are subordinate to it. Feeling gives focus to the internal intuitive process. It causes the insights to be people oriented and value centered. INFJs are at home in a symbolic world and in fact are themselves generators of symbols. They are often gifted and persuasive writers. They have implicit faith in their inner insights. They important ones they work on in quiet, gentle but persistent ways. Their faith in intuition can make them tenacious and sometimes downright stubborn. It can also cause them to ignore fatal flaws. They anticipate and sometimes interrupt others.

eF: INFJs need a well developed feeling side. It helps them test out the implications of their insights and to understand how best to work with others to turn insights into realities. Because feeling is focused on the external world, they are quick to sense criticism. Rather than react, however, they are likely to take it inside, where their intuition may see more to it than is there. They are particularly vulnerable, therefore, to criticism and to conflict situations.

At first glance, you may believe that there is no problem in this definition. After all, intuition, like sensing, is a perceiving function, and an INFJ, who would have dominant introverted intuition, perceives first through their intuition and judges second with their auxiliary function extraverted feeling. Myers did say, after all, that what is extraverted defines judging and perceiving.

But there is nothing to suggest that this should be the case when one is directly asked whether or not they prefer to judge or to perceive. This is an arbitrary axiom that contradicts how Myers-Briggs types are tested for on forms, and hence how it has been studied, marketed, and evolved into. A consequence of type dynamics is that it limits the scope of personality into pre-decided patterns that may or may not contradict reality; but looking at reality is unnecessary in this instance.

Brownsword's description of the INFJ is more in line with a person who would see themselves as a perceiver. Despite Brownsword's attempt to incorporate aspects of judging into this description, the profile he has created is that of somebody who prefers openendedness as opposed to closure. This person would seem to be more likely to prefer being spontaneous to being planned, and being more open-ended about their daily life than being systematized; this person would seem to be more likely inclined to leave a decision open rather than to settle it. Brownsword's intention is clear: he wishes to separate his profile's attitudes with a perceiving dominant function blocked by a judging auxiliary function, but there is nothing to suggest that such a person would more likely to identify with judging as a concept more than perceiving. This is, essentially, what Myers-Briggs theory has come to be founded upon. Rather than reconcile what this consistency truly means with regard to one's type, Myers-Briggs as a personality sorting instrument has gone in a different direction with the introduction of "Step II," which interprets the theory's four dichotomies as dimensions, or scales, where one does not have to absolutely identify with one side over the other.

For comparison, we should analyze Brownsword's description for an INFP:

iF: The guiding force in the INFP personality comes from value judgments made internally. Throughout their lives, INFPs reflect on people and things and make, test, apply, and re-examine the powerful values that govern their behavior. Beneath a gentle and often easy-going exterior, they hold tenaciously to an inner core of values. INFPs will become rigid and unbending whenever these are violated. Intuition supports their introverted feeling and is subordinate to it. They feel most fulfilled when what they do contributes to a better world for all mankind. Inner values based on a sensitivity to intuitive possibilities causes most INFP to set very high standards for themselves, others and the world. When they judge themselves unworthy, they can withdraw from extraverted activities. Deeply depressed, they may become immobilized. When they have a positive sense of self, INFPs more often than not prefer to express their deeply-held commitments in quiet and unassuming ways. Taking active leadership positions takes a great deal of energy and a powerful dedication to a cause.

eN: When involved in extraverted activities, INFPs naturally and easily access their intuitive skills. Still focused on people, they are quick to find meaning, see possibilities, and discover unusual solutions. They are spontaneous and flexible. Unless their powerful inner values are involved, they seek to understand, not judge.

This is a very peculiar and specific profile, and I would be inclined to say that despite Brownsword stating that "they are spontaneous and flexible," his profile for an INFP would seem more inclined to be a judger. But more specifically, Brownsword seems to be implying that the person behind this INFP profile behaves like a judger when alone, but behaves more like a perceiver when "involved with extraverted activities." This person would likely see themselves as a perceiver, but the preference may not be strong—regardless, this should be unusual for an INFP profile.

This peculiarity is not necessarily a fallibility of Myers-Briggs theory as much as it simply shows the profile's ambivalence along the judging and perceiving axis. Whether or not the MBTI characterizes this behavior in a sufficient manner is debatable, but the MBTI would be valuable in analyzing this behavior because the profile's ambivalence (judging alone; perceiving with others) is placed along an axis that sufficiently describes this behavior in simple terms. In other words, a different framework may not necessarily describe this behavior in a way that can be polarized as well as the MBTI polarizes it.

misleading assumptions

chapter 3

The Internet has shaped the modern era in ways that would have been absolutely unprecedented just a few decades ago, when Myers-Briggs theory was still a fairly new development. Perhaps the most relevant way the Internet set the course for its development (and hence, type dynamics development) is in how much more accessible it had become. The floor had now opened up, and no longer were academics and researchers the only people theorizing.

However, this process did not happen overnight. Type dynamics, or what have come to be called "the cognitive functions," were not an immediate hit online, and it would take time for them to gain the recognition they have today. The era where anything at all became fair game had not occurred yet; type dynamics needed to be propelled forward into the public domain.

Linda Berens is a key figure in the promotion of type dynamics. Her works Dynamics of Personality Type: Understanding and Applying Jung’s Cognitive Processes, oublished in 1999, and (with Dario Nardi) Understanding Yourself and Others: An Introduction to the Personality Type Code, published in 2004, introduce a type dynamics model influenced by Beebe (the creator of a popular eight function model). Jack Falt writes the following in his review of the former publication:

This is another book in the Understanding Yourself and Others series developed by Linda Berens. In this booklet the author is moving to the next step of understanding of Temperament and Psychological Type into the dynamics of each type. In her concern for everyone to find their best fit, her style is to use the process of learning about dynamics as a way of checking to see if each person has really found his or her True Type. Also, for her it is a very important component of understanding Psychological Type.

The booklet is intended as a resource for Psychological Type facilitators to use in conjunction with their workshops or individual counselling. It gives participants some excellent material for further self study. For a subject this complex most people new to Type would need the guidance of a facilitator.

The booklet outlines Jung’s basic theory and how he never intended to break down the personality into component parts. The work of Briggs and Myers and their indicator seemed to divide up each personality into four of eight preferences. This was only their way of helping people identify their type. They didn’t intend for the process to stop there. Berens is one of many, who in recent years, is trying to redress this imbalance and help individuals and facilitators understand the greater complexity of Type and how each of us is a living system, not just an accumulation of preferences…

…Overall, I see this book as a very valuable resource, particularly for those who are trained by the Temperament Research Institute. Others may find a good deal of useful information when they are presenting Jung/Myers theory material. There are only a couple of other books that deal extensively with type dynamics and Linda Berens has added one that is well worth considering.

Berens writes from a familiar perspective where "Type" is a greater concept that transcends what people say about it—the concept exists and it is something that can be discovered. She expresses this in the introduction in her book with Nardi: "In the 1940s, Isabel Myers began developing a self-report questionnaire—the Myers-Briggs testing instrument—that could help people find where they fit in Jung's theory. The use of this instrument has led to an almost universal understanding that there are sixteen basic personality types, each of which can be 'named' by a four-letter personality type code." This may be one of the reasons why she, like Brownsword had earlier done, conflates Jungian theory with Myers' work; to her, these are difficult to separate because they are intertwined. It leads to misleading information like the following—an excerpt taken from the same book:

Using metaphors for names, Jung described two kinds of cognitive processes—perception and judgment. Sensation and Intuition were the two kinds of perception. Thinking and Feeling were the two kinds of judgment. He said that every mental act consists of using at least one of these four cognitive processes. Then he described personality types that were characterized by using one of the processes in either the extraverted or introverted world…[Isabel Myers and her mother, Katharine Briggs,] had to take what Jung had seen as an integrated whole personality pattern and try to figure out how to ask questions to get at that whole. They chose to focus on Jung's notion of opposites and force choices between equally valuable psychological opposites…the purpose of this book is to help you understand how the type codes represent patterns of how we use the eight cognitive processes.

Now for context: Berens and Nardi are referring to Jung's notion of "irrational functions" and "rational functions." He occasionally exchanges these terms for the words "perceiving" and "judging" respectively, but it would be unusual to equate this with Myers' concepts of judging and perceiving. Jung is very abstract in how he uses these concepts, while Myers is more literal; they do not translate interchangeably. For example, Jung's introverted irrational types are much more perceiving than his introverted rational types are judging. Myers' concepts of "perceiving" and "judging" move beyond simple attribution to "thinking & feeling" and "intuition & sensing" attitudes, and the concept of "thinking" or "feeling" is only "judging" (and "intuiting" or "sensing" is only "perceiving") from an abstract point of view that would not absolutely translate to something like a testing instrument.

Normally, this would be a negligible error. However, Berens and Nardi piggyback onto this idea in order to frame MBTI as an instrument that determines type codes that represent patterns of how we use the eight cognitive processes. The peculiar thing you may notice in this idea is that if Myers and Briggs really intended to create a testing instrument that reflected what Berens and Nardi call "Jung's eight cognitive processes," they would have taken an approach that directly tests for these eight cognitive processes rather than for four preferences along four dichotomies that are only derived from Jung's work.

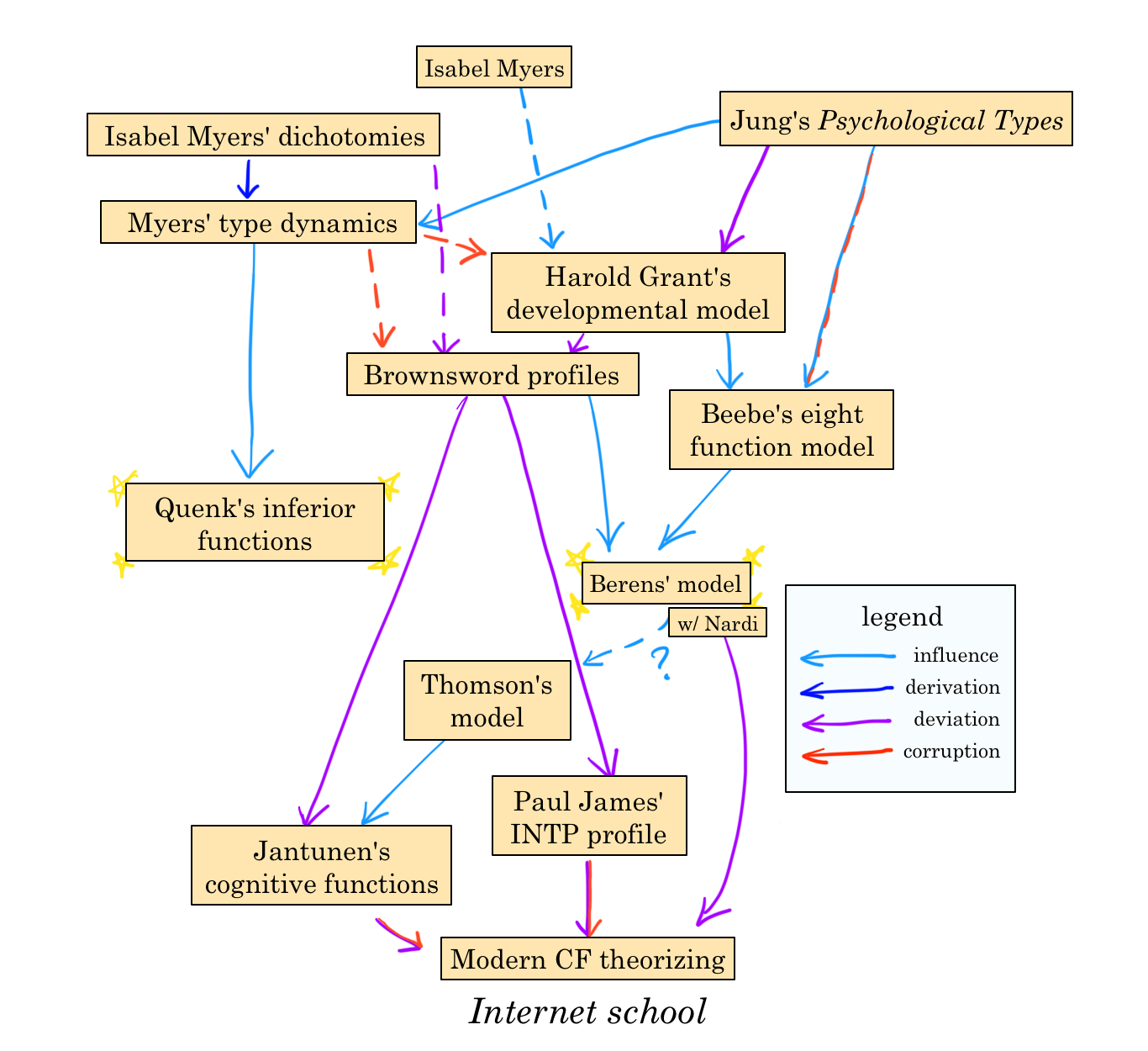

It can be postulated that we have come to refer to type dynamics as "the cognitive functions" through Berens' work—the website cognitiveprocesses.com adapts An Introduction to the Personality Type Code in 2005 and uses Berens' language to describe type dynamics. "Functions" in place of "processes" seemed to gain traction around 2008, though the term "cognitive functions" were first used by Markku Jantunen in 2002.

In short, type dynamics became the misnamed "Jungian cognitive processes," which would then become "the cognitive functions." Berens and Nardi popularized a now common perspective that Myers-Briggs theory is simply type dynamics, which is the product of a categorical error. It is unclear exactly why the cognitive functions had become so popular around this time, but the influences are clearer.

The evolution of how the cognitive functions have evolved is difficult to track. Here is a list of webpages that may have contributed to its evolution:

(March 2000) Paul James' INTP profile

(~April 2001) Robert Winer's Temperament and Personality Typing at gesher.org

(October 2001) timeenoughforlove.org's descriptions of the functions

(February 2002) Jack Falt's Topics for Appreciating Differences

(April 2004) Linda Berens - Five Levels of Coaching

(April 2004) infj.org's Introduction to MBTI™ and Type

(April 2004) infj.org on Type Dynamics

(November 2004) Center for Confidence and Well-Being onType Resources

(~January 2005) cognitiveprocesses.com on The 16 Type Patterns

(September 2005) infj.org on Type Dynamics (updated)

(January 2006) Personality Pathways on The Dynamics of Personality Types: Interpreting the 4 Letter MBTI ® Code of Personality Types

(August 2007) Team Tactix on MBTI Type Dynamics

This list is not exhaustive. These links are easily accessible, hence why I've included them here.

But this has all been the early Internet. Until now, the cognitive functions had only been gaining traction. With the launch of the "cognitive functions" forum on popular typology website PersonalityCafe in 2010, the audience is given a larger soapbox. The evolution of type dynamics that has occurred until now only sets the tone for what the cognitive functions become. With that, we can finally begin to define the cognitive functions.

chapter 4

just what are the cognitive functions?

The cognitive functions are a collection of type theories that have originated with Isabel Myers' idea of "type dynamics," or the interaction between two or more preferences in a Myers-Briggs type, but have undergone severe mutations under the school of thought that recognizes Type as a neurophysiological phenomenon that has been perfected over the years through Jung, Myers, and other such figures' work. This pretense, however, has involved a series of categorical logical errors regarding the relationship between particular theories of personality, and type dynamics have never been able to be verified empirically.

Theories regarding the cognitive functions today are a systematic product of the errors personality theorists in earlier times have made in connecting Jung's work and Myers' work regarding personality. This has led to many typologists today holding incorrect beliefs, such as Myers-Briggs theory being the cognitive functions, or that the cognitive functions used and spread today are necessarily "Jungian" or "Myersian."

In fact, as the cognitive functions have evolved, the definitional boundaries that had constrained them have loosened to the point where there are no longer any universal concepts to analyze when looking at the cognitive functions as a single abstract body. Think of it as a web of people playing telephone. A says something to B, C, and D, B says something else to E and F, E says something to… you get the picture. But the vagueness that pervaded type dynamics regarding how exactly Myers and Jung were connected turned into vagueness regarding what exactly the cognitive functions are.

There are certain rules that have solidified which had once been a great debate; this is about the tertiary function, which now assumes the Grantian direction… but for no particular reason. Before calling toward the anecdotal evidence that exists to ensure that the tertiary function definitely mirrors the dominant function in direction, let it be known that even when the debate had been a thing, anecdotal evidence flocked in either direction for where the tertiary function should really be.

The problem is, however, bigger than that. Anecdotal evidence can go in any which way regarding the functions, and they always have. Anecdotal evidence suggests that the tertiary is introverted, the tertiary is extraverted, or that we "just use all eight functions." It misses the bigger picture—the cognitive functions aren't a grand theory that people can reference and discuss. It's a collection of theories that rely on anecdotal input and loose, subjective definitions that even tend to be inconsistent today. But that is all beside the point—this is all just evidence that personality is simply not neurophysiologically ingrained in a framework universally determined by the "cognitive functions."

But that may be a little misleading. It could be defined in a way in that some particular theorist's conception of the cognitive functions uses which accounts for the reality, and only the reality, of a personality. The constraints may be arbitrary, but if they are true to life, then the system would be accurate. However, I have two big problems with this: 1) it cannot be universalized. 2) the constraints inadvertently limit the potentiality of being into a system that… cannot be universalized. There's just no point to it for somebody who does not want to be limited into looking at type from only one specific framework.

The aim here isn't exactly to discourage you from using the cognitive functions, but to help you understand that they aren't a single, big thing that will help you understand yourself and offer you new insights into the makings of your personality. All you would really be doing is applying some constraints (personality or thinking traits), place it under a conceptual umbrella (a function or type), and relating back to it—in other words, you are not really discovering yourself, but you may be understanding yourself. That's why adopting a detached perspective that looks at exactly what is happening can help you so much more in that journey; wouldn't it be terrible if everything you did were truly premeditated by the processes described in the cognitive functions?

So when you hear Clyde pointing out that Amelia's definition of Fe is incorrect, that Becky's understanding is better, and that you only kind of get it, you now know that you're above that argument. Amelia's Fe is one form of Fe, Becky's Fe is another, and that Clyde has his own silly way of looking at it… and that's it.

The idea presented here, of course, applies to any specific aspect regarding how people conceive "the cognitive functions." Maybe it's how the functions interact; maybe it's how abstractly or literally the functions work; maybe it's which functions are used in which situations; how they're used; how often they're used; how they develop—this is a list that can go on forever. The idea remains clear at its core: the cognitive functions are not what many people think they are.

In the late Internet age, the debate surrounding type dynamics has severely shifted. No longer is the direction of the tertiary function up for debate. Myers-Briggs theory simply is, to many people, type dynamics in and of itself. The interactions and expressions of the functions comprising type are looked at in a different light. Type dynamics aren't a vague, broken link between Jungian theory and Myers-Briggs type theory anymore. It's now the most enticing thing on the market. To many, it's the type theory that actually works—the cognitive functions are deep, complicated, whimsical, and just plain fun to use. There's no testing instrument for it… just use your imagination to understand how they work.

closing remarks

I didn't think I would be writing a conclusion so soon. I had originally anticipated that I would begin with a history of the functions, then offer a perspective, and then show how the functions have evolved into something "extremely funny and absolutely crazy," but I came to realize through writing this that it's extremely unnecessary. "Give someone a fish and you feed them for a day; teach someone to fish and you feed them for a lifetime"—you should now know how to fish!

The greater perspective this may lend you to is that type theories should be treated in isolation rather than putting them all together to complete a One True Type. It was because of this mistake that type dynamics went severely astray, and dealing with ironing out the assumptions later on can be a troublesome task. Jung had his theories, Myers and Briggs had their theories, Grant had his theories, Brownsword had his theories, Berens had her theories, etc. etc. You can, of course, type yourself according to each theory they'd had, but! there isn't a true type waiting for you at the end of the rainbow.

"But they actually work!" should take on a different meaning to you now. You may now be better aware of the idea that type theories are just series of definitions and boundaries that are applied to a whole that is so much more complicated than the sum of what they imply.

And guess what? That can be really liberating.

I didn't think I would be writing a conclusion so soon. I had originally anticipated that I would begin with a history of the functions, then offer a perspective, and then show how the functions have evolved into something "extremely funny and absolutely crazy," but I came to realize through writing this that it's extremely unnecessary. "Give someone a fish and you feed them for a day; teach someone to fish and you feed them for a lifetime"—you should now know how to fish!

"But they actually work!" should take on a different meaning to you now. You may now be better aware of the idea that type theories are just series of definitions and boundaries that are applied to a whole that is so much more complicated than the sum of what they imply.

And the greater perspective this may lend you to is that type theories should be treated in isolation rather than putting them all together to complete a One True Type. It was because of this mistake that type dynamics went severely astray, and dealing with ironing out the assumptions later on can be a troublesome task. Jung had his theories, Myers and Briggs had their theories, Grant had his theories, Brownsword had his theories, Berens had her theories, etc. etc. You can, of course, type yourself according to each theory they'd had, but! there isn't a true type waiting for you at the end of the rainbow.

And guess what? That can be really liberating.

references

Berens, L. V., & Nardi, D. (2004). An Introduction to the Personality Type Code. Telos Publications.

Brownsword, A. W. (1988). Psychological Type: an Introduction. Human Resources Management Press.

Brownsword, A. W. (1999). It Takes All Types. Baytree Publication Co. for HRM Press.

Falt, J. (n.d.). “Book Review by Jack Falt: Berens, Linda V., Dynamics of Personality Type: Understanding and Applying Jung’s Cognitive Processes, Huntington Beach, CA: Telos Publications, 1999, ISBN 0-9664624-5-9, 60 Pp.” Dynamics of Personality Type - Berens, users.trytel.com/jfalt/Rev-per-type/dyn-ber.html. Retrieved April 23, 2019.

Geyer, P. Developing Models and Beliefs: Reviewing Grant, Thompson & Clarke's Image to Likeness after 20 years of life and type.

Geyer, P. (2009). Developing Type: A history from Jung to today.

Geyer, P. (2013). J-P — What is it, really? How it came about, what it means, what it contains, its interpretation and use.

Green. C. D. (1999). Classics in the History of Psychology -- Jung (1921/1923) Chapter 10, 30 Nov. 1999, psychclassics.yorku.ca/Jung/types.htm. Retrieved April 23, 2019.

Jeffries. W. C. (1991). True to Type: Answers to the Most Commonly Asked Questions About Interpreting The Myers-Briggs Type Indicator. Hampton Roads Publishing.

Jung, C. G. (1964). Psychological Types: or, the Psychology of Individuation. Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Myers, I. B. et al. (2003). MBTI Manual: a Guide to the Development and Use of the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator. CPP.

Kroeger, O., & Thuesen, J. M. (1989). Type Talk: the 16 Personality Types That Determine How We Live, Love, and Work. Delta.

Myers, I. B. (1980). Gifts Differing. Consulting Psychologist's Press.

Thomson, L. (1998). Personality Type: an Owner's Manual. Shambhala.

Reynierse, J.H. (2008). The Case Against Type Dynamics.

Reynierse, J. H., & Harker, J. B. (2008a). Preference multidimensionality and the fallacy of type dynamics: Part I (Studies 1–3). Journal of Psychological Type.

Reynierse, J. H., & Harker, J. B. (2008b). Preference multidimensionality and the fallacy of type dynamics: Part II (Studies 4-6). Journal of Psychological Type.

Quenk, N. L. (1996). In the Grip: Our Hidden Personality. CPP Books.

Quenk, N. L. (2009). Was That Really Me?: How Everyday Stress Brings out Our Hidden Personality. Davies-Black.

Sharp, D. (1991). Jung Lexicon: A Primer of Terms & Concepts. Inner City Books.

Myers (rightly) left the functions behind. https://www.typologycentral.com/forums/myers-briggs-and-jungian-cognitive-functions/75546-else-reject-cognitive-functions-4.html#post2434783. Retrieved April 23, 2019.